[To quote Charles Francis Jenkins in his book ‘Button Gwinnett‘, “It has been necessary in far too many cases to use such expressions as ‘it would appear’ or ‘it is probable’ or ‘it seems likely'”. Like Jenkins, I have tried to adhere to known facts but Button Gwinnett proves to be very elusive when it comes to survivng records of his life.]

Button Gwinnett was the third child born to his parents, the Reverend Samuel Gwinnett, senior, and Anne, his wife. Samuel Gwinnett had married Anne Emes, the widow of Fulke Emes, in 1728. They had two children before Button: a daughter called Anna Maria (1731-1745) and a son named Samuel (1732-1792), who became an Anglican minister, like his father. Samuel and Anne went on to have four more children after Button: Thomas Price (1736-1736) and Robert (1738-1738), both of whom died in infancy, followed by Emilia (1741-1807) and John Price Gwinnett (17–?-1773). The baptism of the latter has not been found as yet but is believed to have taken place before that of his sister, Emilia.

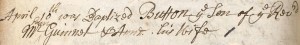

The exact date of Button’s birth is unknown but it was usual to baptise babies at around the age of one month, unless they were sickly at birth, in which case they would be privately baptised at the earliest opportunity. Button Gwinnett was baptised, according to the St Catherine’s parish registers, on the 10th April 1735. There is no reference in the register to a private baptism so it is assumed that Button was born a healthy baby, in or around March 1735. His unusual forename was given to him in honour of his godmother, Barbara Button.

Photograph of entry in St Catherine’s Register, Gloucester, displayed by courtesy of Gloucestershire Archives. Ref: PMF 154/7

This register entry creates a mystery as the church of St. Catherine had been demolished during the 1650s and the second church of that name was not built, albeit on the same site, until the 1860s so the actual baptism must have taken place in one of the surrounding churches, such as St. Mary de Lode, St. Nicholas or St. John the Baptist.

The second question posed by the St Catherine’s register entry is why the record should be in the St. Catherine’s parish at all, when Samuel was the vicar of Down Hatherley, a small village just north of the city of Gloucester. It is thought that Samuel and Anne had a town house in the city at that time and Anne would have been staying there to have access to the best care when her child was due. If the town house were in the St. Catherine’s parish that would, at least, answer the second question.

Having recently checked some of the rental records of the Diocese of Gloucester and the Gloucester Borough Council, it is apparent that Samuel did rent property within the city. This would explain why the baptisms of his children took place in several Gloucester parishes. Generally, it is not yet known where the family actually lived but it is known that Samuel was renting a house at 10 College Green in 1741.

So Button grew up in the city of Gloucester with his brothers and sisters and probably travelled to Down Hatherley with his father at various times. At some point, the family were joined by a young relative, a girl called Arden Price, whom Mrs Gwinnett had taken in to the family home.

Around the age of seven, it is most likely that Button attended a local school. He obviously had a good education, given his later political career. Tradition records that he went to the College School, now called the King’s School, which was then held in the schoolroom in Gloucester Cathedral. His older brother Samuel was recorded in the admission register in 1739 when he was 7 years old but there is no similar entry for Button. However, that is probably because the register was not completed properly at the time; there are few or no entries for the years between 1740 and 1748.

It has also been suggested that Button was a chorister at the Cathedral but a check of the Treasurer’s Accounts for the relevant period proves this to be untrue – the choristers were named every year and the amount they were paid was recorded. Button was not one of them.

Button’s father, Samuel senior, is believed to have attended Glasgow University where he gained his M.A.; his older brother, Samuel junior, went to Oxford University after he left school, as did several other members of the Gwinnett family, but there is no evidence to indicate a university career for Button. Tradition has it that he went to Bristol to work with his uncle, William Gwinnett, who was a grocer in the city. He does not appear to have been officially apprenticed to his uncle as no record has been found but there is a record of Button Gwinnett being apprenticed to John Weston Smith, an ironmonger from Wolverhampton, on 2nd May 1754. When this happened, Button would have been 19 years of age, which was very late to begin an apprenticeship – most took place when the boy was 14 years old.

So why would Button suddenly move from Bristol to Wolverhampton and start an apprenticeship with an ironmonger at such an advanced age? Maybe his uncle, William, felt he needed a broader training. Perhaps Button showed an interest in trading across the Atlantic Ocean; William had travelled to America at least twice in the 1720s and was believed to be trading with the new world but by 1754, he was approaching 70 years of age. Perhaps he was planning to retire from the merchant’s business. Maybe William had contact with John Weston Smith through his trade at Bristol docks. Not enough is known about William’s life to be sure of why Button left Bristol but there is no doubt that he did go to Wolverhampton.

It was in Wolverhampton that Button met the girl who was to become his wife. She was Ann Bourne, the daughter of a local grocer, Aaron Bourne. On 12th April 1757, 22 year old Button applied for a licence to marry Ann and, one week later, on 19th April, they were married at the Collegiate Church of St. Peter in Wolverhampton. Since apprentices were not permitted to marry, it is assumed that Button’s apprenticeship to John Weston Smith had ended.

The next record relating to Button Gwinnett was created on 24th October 1757 when he was admitted as a Freeman of the City of Gloucester, as had been several other members of the Gwinnett family, including his older brother, Samuel, junior. The entry merely names Button and states that he was the son of Samuel, a clerk. It does not record that he had completed any apprenticeship, nor does it state that he paid ‘a fine’ or was admitted as a freeman ‘by gift’ of the council. Presumably he was admitted based solely on the fact that he was his father’s son.

During the next five years, Button and Ann had three children, all daughters. Amelia was baptised in St. Peter’s church, Wolverhampton on 27th February 1758, followed by Ann who was baptised there on the 14th May 1759. Both of these girls died young: Ann died first and was buried in December 1759 in the churchyard of St. Michael and All Angels in Tettenhall, just outside Wolverhampton. Her older sister, Amelia, died a couple of years later, in March 1762 and was buried close to her sister. Two months before Amelia’s death, Button’s wife, Ann, had given birth to their third daughter, Elizabeth Ann. It must have been a very difficult time for the young family.

Button began to widen his horizons and looked towards trading with America on his own account. Details of the next few years are vague, on the whole, but we do know that he had received a legacy of £100 in the will of his godmother, Barbara Button, in 1755. Perhaps this gave him the wherewithal to invest in shipping.

There is a record of Button’s part ownership, with Matthias Neale, of a brigantine called Recovery, which had been registered in Barbados on 20th January 1764. It weighed 60 tons, had a crew of 5 and no guns. That year, the ship carried ballast from Havana, in Cuba, to Bridgetown in Barbados, under its master, John Mills.

By the 7th September 1765, Button, described as ‘of Savannah’, had become the sole owner of a brigantine called Nancy. The Nancy was again 60 tons, with no guns but, this time, it had a crew of 8. It was registered in Barbados. Under the same master, John Mills, the brigantine had travelled from Pensacola, in Florida, to Savannah in Georgia with a cargo of groceries, medicines, tobacco, saddles, etc.. Two months later, with a new master, John Forster, the Nancy left Savannah for Antigua with a cargo of timber.

One year later, on 6th November 1766, the Nancy entered Sunbury in Georgia, from St. Croix, in the Virgin Islands, with a cargo of sugar. By 25th June 1767, the Nancy left Savannah for Bristol, with a cargo of rice, deerskins, staves, tar and pitch, with Philip Conway as master and a new owner, John Powell of Great Britain. It is believed that the Nancy was confiscated from Button Gwinnett to pay for his debts.

Sometime between 1762 and 1765, Button moved to America permanently, leaving Ann and Betsy (Elizabeth Ann) behind in Wolverhampton. He traded up and down the US east coast from Newfoundland to Jamaica. His dealings always seemed to be dubious – he was good at borrowing money and not repaying it.

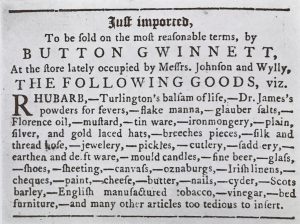

In 1765, he settled in Savannah where he ran a grocery store. A newspaper advertisement shows the types of goods he sold there.

Later that year, in October, he bought the lease of St Catherine’s Island from Rev. Thomas Bosomworth, almost entirely on credit. This qualified him, as a landowner, to be an elector and, eventually, a politician.

Button’s wife, Ann, visited in 1767. The house, built of ‘tabby’ (compressed shells and mud, similar to our wattle and daub) and the island itself would have been a great shock to her, different from anything she had experienced.. Not surprisingly, she returned to England after a year.

In 1768, Button was appointed a Justice of the Peace and then elected to the Commons House of Assembly for the parish of St John’s – the start of his political career.

By 1770, he possessed the Barber Islands. However, symptomatic of Button’s financial activities, in April 1770, a warning notice appeared in the Georgia Gazette, placed by one Anthony Lamotte, stating that he owned the islands, that Button had sold them to him but not given him the documentation and he feared he was trying to sell them for a second time! Presumably also due to lack of funds and a need to deal with his debts, in the same year, Button leased St Catherine’s Island to Edward Mease.

In 1771, Ann returned to America, this time bringing Betsy with her. In 1773, Button had to sell his lease of St Catherine’s island back to Bosomworth to pay his debts. He was allowed to continue living there.

The First Continental Congress was held in Philadelphia in 1774 but no representatives were sent from Georgia. When the Second Continental Congress, it was only attended by Dr Lyman Hall.

In 1775 war broke out between the British and Americans. The following year, Button was elected as one of five delegates from Georgia to represent the state at the Grand Continental Congress, along with Archibald Bullock, John Houston, Lyman Hall and George Walton..

20 May 1776, Button attended the Continental Congress with two of his colleagues. He was then appointed to two committees. On 4th July 1776, the draft version of the Declaration of Independence was signed, the final version being signed on 2nd August. Button’s signature, worth a small fortune these days due to its rarity, was second on the document.

In a state election, Button Gwinnett was selected to be Speaker of the Convention which meant that, amongst other things, he was in charge of writing the constitution for Georgia. In February 1777, the new constitution was passed but, despite his political success, Button still had ambitions – this time he wanted to lead the Georgia Brigade of Rangers although he had no military experience whatsoever.

However, this position was granted to Lachlan McIntosh, an old enemy of Button’s, but, in his position as Speaker, Button was able to re-structure the militia, removing those he did not like and thus weakening its ability to fight effectively. This did nothing to improve the relationship between Button and Lachlan. The situation continued to fester.

Meanwhile, the Provincial Congress adjourned and government of the state reverted to the Committee of Safety under the President, Archibald Bullock. But Bullock died suddenly and, on 4th March 1777, Button Gwinnett was elected President of Georgia in his place. This position included that of Commander in Chief of the Militia – he was at last in charge of the army!

He hoped to lead them on a new expedition against Florida where many loyalists had settled, the First Florida Expedition having been a failure, but the force was not strong enough to succeed on its own. Rather than approach McIntosh for support, Gwinnett went over his head and asked help from General Howe. This was refused as it was considered the expedition would not be successful and Gwinnett found himself in the position of being unable to ask McIntosh for help at that point as he could not go against the orders of his superior officer.

A few days after his election as President of Georgia, Button had received notice that one William Panton, with the help of George McIntosh, had shipped an illegal cargo out of the state and it was recommended that Button should arrest the latter, which he did. But George was Lachlan’s brother and Lachlan declared Button to be a man seeking personal and political revenge.

For various reasons, the Second Florida Expedition was also a failure. Back in Savannah, the animosity between Button and Lachlan continued. The Assembly met again in May 1777 and proceeded to elect a new Governor to replace the President. Gwinnett was unpopular with both his opponents and also with many of his previous supporters who were beginning to realise his many faults. On 8th May, John Treutlen was appointed the first Governor of Georgia. A flawed enquiry found that Gwinnett’s conduct had been correct and therefore McIntosh’s behaviour had been wrong. Needless to say, McIntosh was incensed at the finding.

On 14th May, in front of the whole Assembly, McIntosh called Button ‘a scoundrel and a lying rascal’! That evening, Button wrote to McIntosh, challenging him to a duel for the insult and wrote a rapid will. The next morning, the two men met, with their seconds, just before sunrise. The two men stood, face to face, about 10 feet apart. Lachlan was shot in the thigh but Button had his leg smashed above the knee. The seconds decided honour had been satisfied and the participants left to tend their wounds. Lachlan recovered but, three days later, Button died of gangrene.